- timcloudsley@yahoo.co.uk

- |

- |

Español

Español- |

English

English- |

Prosa Académica y Filosófica

Los inmortales de Irlanda

Ireland´s Immortals. A History Of The Gods Of Irish Myth, by Mark Williams, Princeton University Press, 2016, xxx + 578pp., $39.50 (cloth)

(To be published in The European Legacy in 2019)

Any review of a book like this is bound to be selective, as it contains such detail, such vast swathes of scholarly research, that one can only attempt an overview of some of its over-arching theses. However, such an effort must include certain details, whose selection really only reflects the reviewer´s choices. Suffice it to say, the book is magnificent, worth the enormous energy required of the reader whoever he or she might be, whether specialist or layman.

I will attempt such a review, commenting at times from outside the specialist fields involved, in a thorough-going fascination with the work; and also remarking upon its great importance from my point of view.

The transition from “pre-historical”, oral societies to “historical”, literate societies is a general world-historical phenomenon. The particular form which this process took in Ireland, between the fifth to seventh centuries CE, is very well explicated in Mark Williams´ book. Before the coming to Ireland of an alphabet there existed ogam, a system of notches used originally for inscriptions along the edge of a stone. Perhaps this can be compared with the oracle bones used in Ancient China, or quipos, the system of ropes with knots that represented a kind of early notation in pre-Hispanic Peru. Williams discusses the coming of literacy with the Latin alphabet to Ireland from Roman Britain, which resulted in writings in Latin, and the Irish language using the Latin alphabet. By around the year 700 C.E., three centuries after the process of conversion to Christianity began, “pagan divinities began to appear in a vibrant literature written in Old Irish.”(4-5) The author continues:

“Two questions immediately present themselves. Why should a Christian people be interested in pagan gods at all? And what was the relationship between the gods whom the pagan Irish had once venerated and the literary divinities who thronged the writings of their Christian descendents?”(5)

The coming of Christianity, along with the first real writing about Old Irish theology and mythology, when these were now actually fading away, so that such writing was inevitably tainted with Christian biases within the thought processes of the literati, can be compared to many examples of chronicles written by people, whether sympathetic to an “old religion” or not, in many parts of the world, whose accounts may be untrustworthy in many respects for scholarly analysis. This is obviously true of Greco-Roman writings about earlier religions, but also in the remarkable book called Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno, written by Guaman Poma as a native Andean within Quechua society in post-Spanish Conquest colonial Peru.

Guaman Poma wrote in the language of the foreign conqueror – Spanish, and using many European classical tropes, talked, among many other things, of the conversion of the Quechua people during the first hundred years after the Spanish conquest. He includes fantastic and historical events intermingled in his time within the popular imagination, yet at the same time Guaman Poma sought to conform to Renaissance norms of historical truth.

In his discussion of the pre-historic síd in Ireland, Williams speaks of these as supernatural “hollow hills” which were not of a single parallel dimension, but rather consisted of several different and apparently unconnected, parallel worlds. These pre-Christian grave-hills were Otherworlds; their inhabitants looked like human beings but were different: all was hallucination, like something created by digital computers today; or, more like it something appearing in an hallucinogenic vision induced in South American shamans by Ayahuasca. It is a fundamental issue for debate, without a clear conclusion, whether the supernatural beings of these síds really formed part of the pre-Christian Irish religion.

There are surviving statements by Christian medieval writers that connect mound-dwelling beings or druids to pre-Christian gods. The first is an account of Patrick around 690 C.E. by Tirechán, in which Patrick meets the two daughters of the king of Tara. The two princesses imagine the strangers to be supernatural beings or men of the síd-mounds. The saint quickly disabuses them and answers their charmingly naïve questions about the nature of his God. They immediately become Christians, are baptized, and on receiving the Eucharist for the first time, expire. The Adventure of Connlae, written perhaps a little later by an anonymous author, is set after the birth of Christ but before the coming of St. Patrick. Connlae meets a strangely dressed woman who says she is from the land of the living ones, and summons him to the “Plain of Delight” where there is no sickness or death. The magical druid Connlae goes with her to her supernatural realm and becomes immortal.

Tirechán depicted a by now outmoded paganism that centres around a belief in nature-dwelling gods who are reminiscent of Roman numina. This is how a learned bishop a hundred and fifty years after the end of paganism, imagines an innocent belief in nature gods. Perhaps he was influenced by St. Paul´s statement that even gentiles could infer the existence of God from the visible creation around them.

Williams considers the views taken in medieval Europe towards the Norse Gods, and those parts of the Old Testament which imply that in Israel other gods besides God really had existed; about which passages Augustine of Hippo affirmed that indeed such pagan divinities had been “real, albeit demonic, spiritual beings.” Williams continues that, “like the Norse pantheon, the Irish gods were local figures, often associated with particular features in the landscape; they never occupied the lofty cosmological and allegorical roles which medieval philosophy assigned to the gods of Mediterranean antiquity.”(493) The author adds that some medieval writers made analogies between classical and Irish deities, but this attitude only really flourished in the late nineteenth century CE.

Thus the first written Irish literature on Irish gods was medieval. Later modern and romantic Irish literature of the 18th and 19th centuries – fantasizing about the ancient myths, personages and so on – contained some superb literature tangled up with the politics of colonial subjugation in Ireland within English/British colonialism, but also with the complex, convoluted relationships between Catholicism and Protestantism.

Irish nationalism has had and does have a unique emotional power. There may be a crackpot element in George Russell´s and W.B. Yeats´ almost childish fantasies (and Russell´s paintings of spirits and faeries are rather corny – as Sean O´Casey pointed out – though also extremely striking), somewhat like a child who believes in all sorts of spirits, beings, animals etc. who dwell under his bed, which are moreover always changing. Williams notes that “the distinctiveness of the Irish setup lies in its restless refusal to resolve. This could be richly exploited; writers could and did fine-tune the ontology of these supernatural figures to suit their literary purposes, sometimes cleverly crosshatching different takes on their nature within a single text…… (this) enabled literary deliberation upon human nature – its pleasures, potentials, and pitfalls, its limits and excellences, and its ultimate fate. In medieval Irish literature elusiveness and ambiguity occupy a position of high aesthetic value, and the hazy status of the native supernaturals was ideally suited to the creation of such effects.”(493) Williams suggests that the pre-Christian Irish probably had numerous local deities, the majority of which were lost during the conversion, leaving only a small core of literary figures. During the Middle Ages these multiplied into a host of síd-folk, which later again underwent a thinning down, leaving again in modern times “a small clutch of ´ancient´ gods.”(493)

Angela Carter observed that: “the realm of faery has always attracted nutters, regressives and the unbalanced.” (Quoted 503) But this attempt to create a national imaginative fantasy world, wrapped into an unclear but intense set of ideas about the Irish identity, its very long past, Ireland´s immense historical suffering; and its hopefulness for the future, is extraordinary. It succeeds, in a sense, more than those of the other three constituent nations of “Great Britain”, in creating a kind of unified national literature, which culminates in such writers as James Joyce, and beyond; without great surprise for anyone who knows something about this history. Fantasy, whimsy, alternating moods of intense nostalgia, melancholy, jollity, invention, and redemption: this is all there throughout the long tradition of Irish literature, beginning in the 6th Century and continuing through to now. Williams succeeds in bringing to life a pulsating sense of “Irishness”.

The important point is that supposedly digging back into pre-Christian Irish religion has had an emotional nationalist intensity, as if the memory and resurrection of this mind-set in new and modern forms is part of the resistance against English/British domination, in culture and religion as well as in colonial/imperial economy and polity. This is different from in England, where enthusiasm and involvement in ancient “Druidic” religion for example has emotional and spiritual significance for its followers, but not a “national” dimension in the same way as for Ireland. For Scotland such pursuits do have a “national ” significance for “identity” and culture, but as Williams follows it through in the chapter called “Highland Divinities”, there are difficulties with this that are different and greater than in the Irish case.

Thus, from the 1890s Scotland developed its own Celtic Revival, an anti-industrial aesthetic movement centred in Edinburgh, that looked to Ireland for its example. It claimed that the Gaelic Túatha Dé Danaan was a pantheon equally native to the Highlands as to Ireland. According to this view Ireland and Gaelic Scotland had been part of a single cultural and linguistic zone in the Middle Ages, and thanks to James Macpherson´s Ossianic poems, Scotland had been the fountainhead of Romantic Celticism in the English language for more than a century. Alexander MacBain was a pagan survivalist who though that Gaelic society had been Christianized relatively recently, and only superficially. Alexander Carmichael collected a body of charms, prayers, and blessings. His project was to demonstrate that a belittled and beleaguered Gaelic culture was worthy of respect; such respect necessitated for him assumptions about very direct links between present culture and the distant pagan past. He ignored thereby the centuries that had separated Victorian Gaels from paganism (though it is surely possible that some elements of an older culture can remain in a society for many centuries), and the fact that Christianity had arrived in Scotland thirteen hundred years earlier; but lamentations about the vanishing of nature spirits in the face of industrialization were widespread in nineteenth-century Britain. Shelley´s poem “The Woodman and the Nightingale” expresses this feeling most superbly:

The world is full of Woodmen who expel

Love’s gentle Dryads from the haunts of life,

And vex the nightingales in every dell.

The tendency to believe in pagan survivals from more than a thousand years before, was not in fact a characteristic of romantic poets like Shelley, who was simply a pantheistic mystical “Taoistic” poet of the early nineteenth century. Here we are more concerned with ideas of “Survivals of Paganism”, about which Black has written a witty summation of thirty years of debate, in an article entitled “I Thought He Made It All Up.” (364).

As Williams puts it: “it was the creativity (of Russell and Yeats) between 1885 and 1905” that gave rise to the Irish Literary Revival. (310) There is a Shelleyan feeling in Yeats, shared by some of his contemporaries and followers, “that the veil of familiarity…. when stripped from the world, lays bare the naked and sleeping beauty which is the spirit of its forms”. (Abridged from Shelley´s “A Defense of Poetry”.) This, combined with utilitarian materialism, along with a soul-destroying and mind-numbing mechanistic and technical division of labour, has destroyed the capacity of people to enter into and be overcome by the divinity and beauty of nature.

A most beautiful, and extraordinary idea of W.B. Yeats was his notion of “immortal moods” - clusters of mingled thought and feeling, rather like musical chords, that existed in the divine mind, eternal and disembodied, like Platonic forms. These become incarnate in the visible world and in time, by means of human emotions, which they govern and in which they participate. A well-chosen symbol should resonate like a tuning folk with a particular, immortal mood, consciously drawing its influence across into the human world. Yeats must have known Shelley´s poem Epipsychidion, in which the poet meets a divine woman, whose “Spirit was the harmony of truth”. There seems here also to be a throwback from Shelley´s enchanted island in which,

….like a buried lamp, a Soul no less

Burns in the heart of this delicious isle…

to the monastic poem The Voyage of Bran:

The colour of the ocean on which you are,

The bright colour of the sea on which you row:

It has spread out gold and blue-green;

It is solid land.

George Russell´s concern was to show how an infinite, impersonal, and ineffable deity could have given rise to the many spiritual beings which he saw in visions:

“His solution was two parts Hinduism to one part Kabbalah, with a dash of Neoplatonism. From the infinite primordial One… emanate the unmanifest male Logos, or Divine Mind, and the female World-Soul…. This primal couple then eternally mingle and from them proceed myriads of manifest beings (including human souls)…. and the ´Light of the Logos´, a universal shaping force of divine energy in the form of love.”(324)

Yeats came to doubt what he increasingly came to see as religious mania in his friend Russell, a millennial excitability that was pushing the latter towards mental breakdown. And he became seriously concerned with the suicidal imagery in Russell´s visions (for example Russell´s asserting that he dreaded seeing the Sidhe-beings associated with water, given his recurrent urge to drown himself), as well as his apparent call for violent action: “The Gods have returned to Erin and have centred themselves in the sacred mountains and blow the fires through the country.” “The hour has come to strike a blow….”(quotes 343)

In an extraordinary story called Rosa Alchemica, Yeats was apparently ironically criticizing what he felt were Russell´s formless and fanatical hopes for a pagan renaissance (though he was also ironizing his own doctrine of the gods as eternal signatures or moods), together with his growing suspicion of Russell´s “woozy deprecation of ego and outline”. Yeats himself was coming to the view that the role of a great poet was to be ´the subconscious self´ of his people, uttering forgotten truths, bringing these up from the depths, as the mouthpiece of the collective unconscious of the nation. But in Rosa Alchemica he writes:

“A mysterious wave of passion, that seemed like the soul of the dance moving within our souls, took hold of me, and I was swept, neither consenting nor refusing, into the midst. I was dancing with an immortal august woman, who had black lilies in her hair, and her dreamy gesture seemed laden with a wisdom more profound than the darkness that is between star and star…; and as we danced on and on, the incense drifted over us and round us, covering us away as in the heart of the world, and ages seemed to pass, and tempests to awake and perish in the folds of our robes and in her heavy hair.

“Suddenly I remembered that her eyelids had never quivered, and that her lilies had not dropped a black petal, nor shaken from their places, and understood with a great horror that I danced with one who was more or less than human, and who was drinking up my soul as an ox drinks up a wayside pool; and I fell, and darkness passed over me.”(Quoted 344)

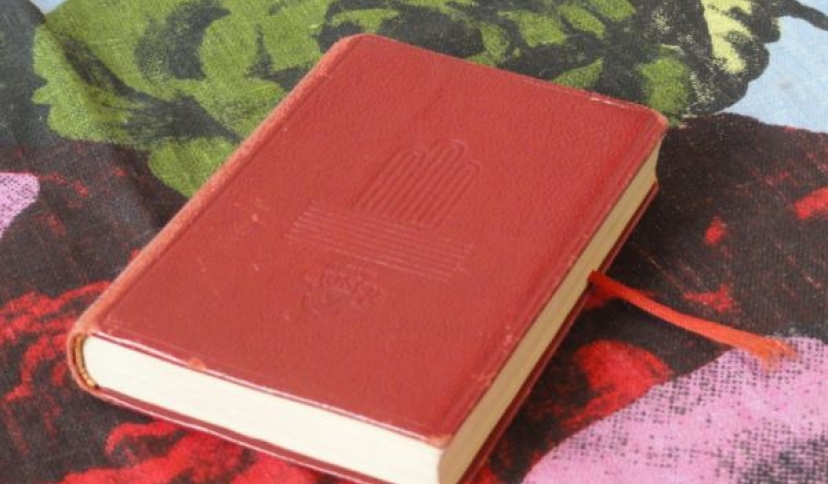

In the last chapter of Williams´ book, called “Artgods”, he tells a disturbing story about a rather superb and beautiful statue (there is a photo of it on page 491) of the sea-god Manannán in his boat, arms raised to command the sea. This fibreglass and stainless steel piece of public art by John Darren Sutton looked down from Binevenagh Mountain, in Co. Derry, Ulster, over the eastern edge of Lough Foyle. It was destroyed one night as recently as in 2015, by an unknown person or persons who, after breaking it up and throwing it down a cliff, replaced it with a wooden cross with the inscription YOU SHALL HAVE NO OTHER GODS BEFORE ME. The irony in this horrible incident is that in “The Voyage of Bran”, its learned author, a monastic cleric, had thirteen hundred years before depicted Manannán as a substitute for Christ. Evidently he and at least some fellow clerics had not found the concept too heretical, though perhaps the author of “The Wasting Sickness of Cú Chulain” would have agreed with the twenty-first century vandal or vandals since he “dismisses the gods as demons from before the Faith, prone to beguiling mortals with delusory phantasmagorias.”(490)

Williams says that the violent acts described above occurred just as he was finishing his book, and they brought him to some final observations: that he “began not with aspirations to complete coverage but with a series of questions.”(490) These were who and what the gods of Irish myth are, why they are so exceptional, what has been the nature of the imaginative investment made in them, and finally how they have been reconstituted as a pantheon in modernity. Perhaps I will conclude this review with a reference he makes to “the literary seascape´s potential as a vehicle for a supposedly ´Celtic´ melancholia and emotional turbulence. (´Moananoaning¨ James Joyce´s superb pun (in Finnegans Wake) on the sea-god´s name – comes irresistibly to mind.)” (378)

Tim Cloudsley

timcloudsley yahoo.co.uk

Descargar como pdf